How I started building softwares with AI agents being non technical

At the start of the year, the CEO of Anthropic had made a prediction that 90% of code in enterprises would be written by AI by September. Now that we have crossed September, we now know that the prediction turned out to be false. As Ethan Mollick mentions, he only seems to have been off by a couple of months (this was recently posted by Boris, the creator of Claude Code) where he mentions 100% of his contributions to Claude Code, written by Claude Code!

Last year 2025, by no doubt has been the year of AI agents. And I was tempted right from the beginning to play with this shiny new toy. And as a “technically curious” person, I want to dive right in. Ended up spending most nights and weekends understanding how to build software with AI agents. It was super fun..

Out of the many side projects that I built this year, here are some memorable ones:

- writing platform with proof-of-human authorship, 98% AI usage

- voice dictation tool with dictionary support, and speaker diarization, 98% AI usage

- personal website, customised to my own bespoke taste, 90% AI usage

- dial international phone calls on the web browser, 98% AI usage

Apart from these heavy-duty apps, I also built various micro-tools that served various ad-hoc use cases which include a chrome extension to import X bookmarks as Trello cards, a Windows XP-esque wallpaper with dynamic 3D clouds, an AI chess coach for improving elo score through socratic dialogue, an Obsidian plugin to help me prioritize the worst rough draft of an essay to improve first, and even a Mac-native open source screen recorder.. (all open source, and free for use)

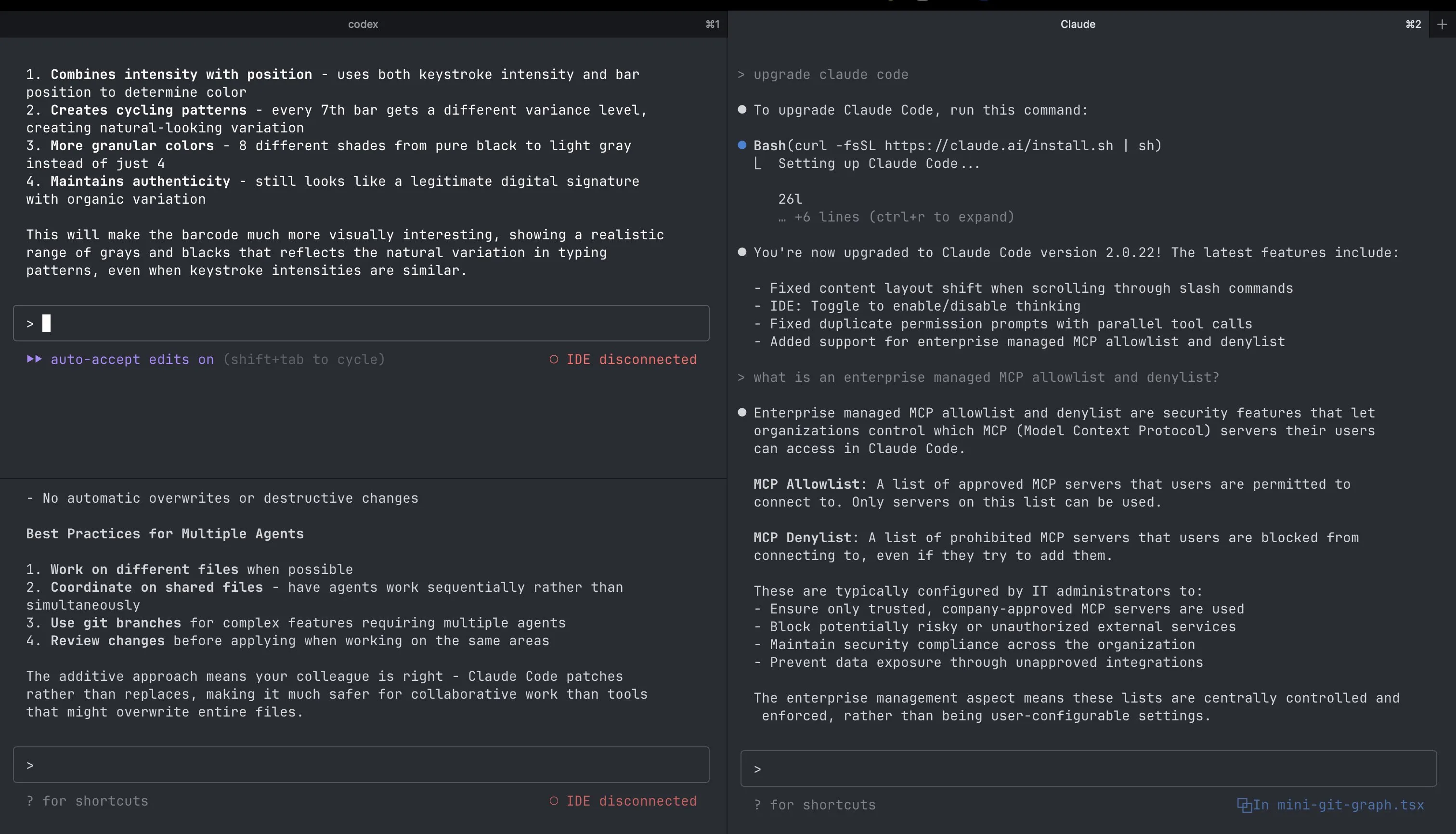

The beginning was quite benign. Early 2025, I felt initially that LLMs could only build toy apps, and were not capable of building anything truly substantial. So I was stuck to creating various one-off prototypes using Lovable and Claude Artefacts to make them. I still wasn’t sure about it’s usage in complex codebases. The only way I was using them was by copy-pasting code snippets to ChatGPT and feeding them back. Then it evolved to simple autocomplete on AI-native IDEs such as Cursor IDE. Then I started using the chat window on the IDEs directly to interact with my codebases. I now run a Ghostty terminal with multiple tabs open with Codex instances.

By this time, mid-2025, the scaling laws were kicking in, and the agents were becoming much more successful in performing longer operations without breaking or hallucinating in between. The recent charts show tasks that take humans up to 5 hours, and plots the evolution of models that can achieve the same goals working independently. 2025 saw some enormous leaps forward here with GPT-5, GPT-5.1 Codex Max and Claude Opus 4.5 able to perform tasks that take humans multiple hours—2024’s best models tapped out at under 30 minutes. With this equipped model capabilities, I was excited to try CLIs and had great success. I hardly look at any code nowadays, not even a code ditor. My current setup looks like this:

It’s all on the terminal with Codex with multiple tasks running on different terminal windows. All I do is, engaging in a socratic dialogue with the models on various aspects: is X more performant than Y? Have you researched on alternative to perform feature Y? Does the API provided by platform Z have any rate limits which need to be considered?…

To some extent, it almost feels like coding has evolved to a higher-level of abstraction, and like how Karpathy sensei mentions in this tweet, “here’s a new programmable layer of abstraction to master (in addition to the usual layers below) involving agents, subagents, their prompts, contexts, memory, modes, permissions, tools, plugins, skills, hooks, MCP, LSP, slash commands, workflows, IDE integrations, and a need to build an all-encompassing mental model for strengths and pitfalls of fundamentally stochastic, fallible, unintelligible and changing entities suddenly intermingled with what used to be good old fashioned engineering”

Building such projects was giving me an intuitive understanding of how something as non-deterministic as a large language model can fit into a deterministic workflow of building software. I slowly moved from being a “no code” person, and with AI agents I moved to being a “some code” person. I still couldn’t write code and defined myself as a “non-technical rookie” to some extent. But with AI agents, it just changed the game, I was able to steer them towards what I wanted to achieve, and build great software.

How I use LLMs now

Here are some lessons I learnt while just jumping into the “AI waters” using LLMs and agents, and learning how to swim with them (as of Jan 2, 2025, things change really fast TBH):

Model usage

- Model usage boils down to economics, with evaluations of tradeoffs between cost and intelligence being done for answering various questions on a frequent basis.. (you wouldn’t really use the most sophisticated model on the leaderboard to figure out how to center a div, for eg.). I now use gpt 5.2-codex-extra-high for complex problems, and gpt5.2-codex-medium for anything else.

- In my initial explorations, I used to be very open ended in deciding which framework I should use. I was going with the defaults which codex gave. Especially when this gets subjective on a well-oiled, well contributed library, or framework which we can trust. I’ve arrived at a sensible set of defaults which I’m comfortable to understand, and almost always use them for various apps. For any web-app to be built, I use this starter kit which is basically Ruby on Rails in the backend, with Inertia for using React on the frontend. It does a good job of bringing together best of both worlds: React and Rails together, and also has great component libraries such as shadcn baked in. For anything mobile, I build on Expo, and for one-off frontend prototypes, I build React/vite apps. Over time, I’ve also gained an intuition on the prowess of each of these frameworks, so I can understand what their limitations are. language/framework and ecosystems are important decisions taken,and hard lessons have been learnt.

- In terms of model selection, I almost always choose Codex over anything else, even Claude Code. Claude Code has great DX, and other utilities such as hooks, skills, commands etc, but Codex seems to just “get” it without any such charades. I was using Claude Code until I saw the brilliance of Codex from Peter Steinberger in his talk at the previous Claude Code Anonymous meetup in London. I’ve never really touched Claude Opus/Sonnet after that.

- Another reason I use Codex is that they’re not as sycophantic as Claude, and pushback whenever necessary. When I make delirious requests.. Codex is like “are you sure you want to do Y, it might break X and Z… here are couple of alternate options a, b and c…”

UI prototyping

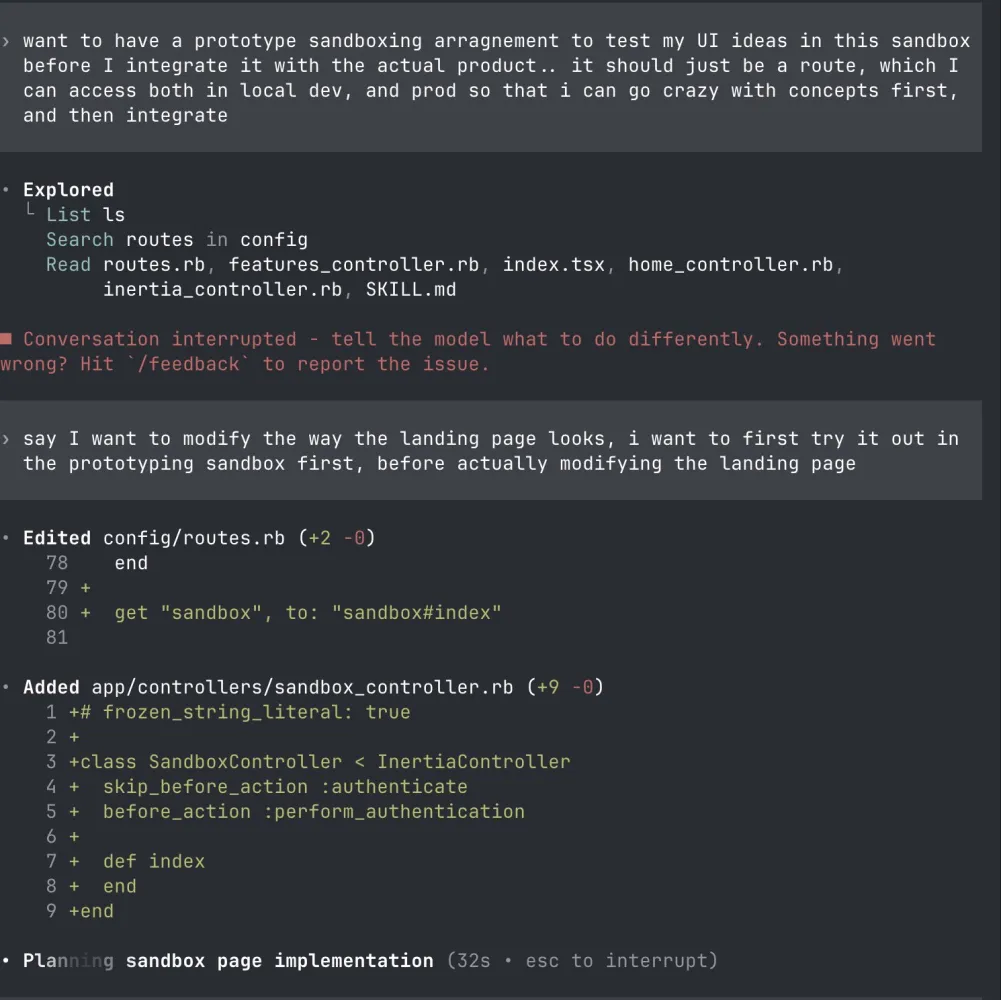

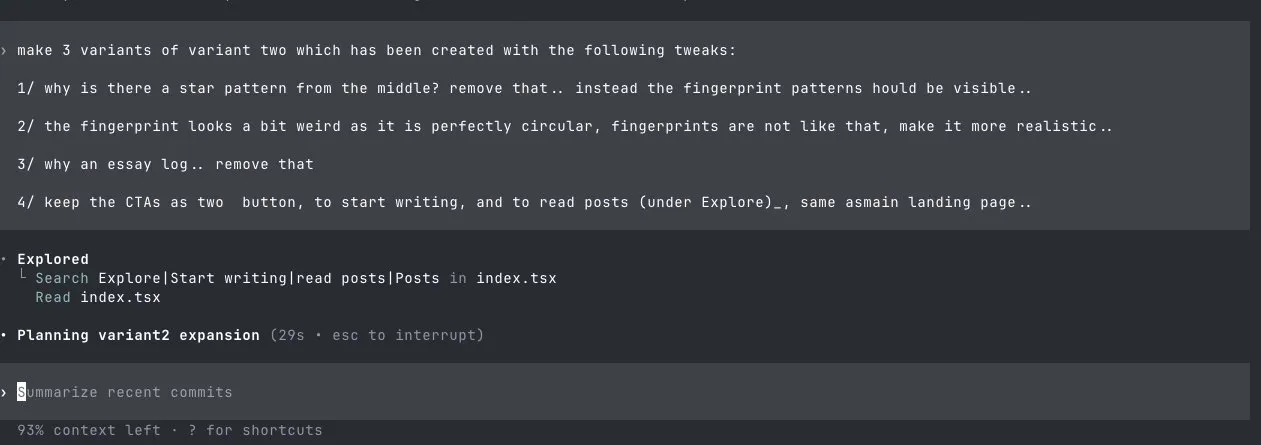

- For UI prototyping, I almost by default ask the model to come up with multiple variants of the same problem. While building the landing page for Signify, I was exploring kinetic typography for expressing the message through type, so I prompted the LLMs to come up with three variants of the same. If the variant 2 “clicked”, I then asked it to branch further, and come up with 3 additional variants of variant 2, before finalising on the direction. I was diverging to converge, and then again, converging to diverge. All these variants I now store them on the /sandbox route for an app, before I integrate with the actual app..

- Another technique for faster UI explorations in a “low fidelity” way is to ask it to generate ASCII diagrams of the UI layouts, and it cooks up something like this, making it easier to iterate on loop.

- For the past three projects that I’ve shipped with AI agents I’ve never touched Figma to communicate anythng at all.. despite years of being ingrained in the Figma-way of building prototypes.. Now I just use excalidraw (to draw loose sketches), ascii diagrams (to generate lo-fi mockups) and prototype sandboxes with good design systems (to generate hi-fi mockups)

Workflows

- I usually parallelize by running multiple tabs with Codex open. I don’t git worktrees or anything of that sort, but in a way I prevent the models from stepping into each other’s toes by means of atomic commits:

Keep commits atomic: commit only the files you touched and list each path explicitly. For tracked files run git commit -m "<scoped message>" -- path/to/file1 path/to/file2. For brand-new files, use the one-liner git restore --staged :/ && git add "path/to/file1" "path/to/file2" && git commit -m "<scoped message>" -- path/to/file1 path/to/file2- For debugging, I almost always copy+paste the dev/production tail logs to ChatGPT and it solves 99.99% of the problems. I’ve heard some of my friends have a much more advanced workflow where they integrate Sentry to log all the errors (I haven’t personally tried this yet, I wanted to cross this bridge when I have no other escape route)

- With AGENTS.md or CLAUDE.md file, I give instructions only on a higher abstract level, as I’ve seen some Twitter folks mentioning that the models almost always bypass the code snippets which are added to the agents file. Think of this as higher level steering instructions. Not too detailed, and not too vague either. I use a variant of this gist for my own purposes.

- With context window optimisation, I’ve been recently understanding that there is a great-dumbening of the model especially when the context window is more than 40% of it’s actual limit, and the best approach then is to start a new chat with the agents, instead of adding more to the same chat session.

- I don’t do compaction of the chat windows as I view them as lossy. In case the chat is more than it’s 40% limit and if I haven’t been able to get the problem fixed yet, I instruct the agent to write a markdown file with the output of all the revisions, changes and decisions made. I then reference this file to a new chat

- No more plan modes. Previously with Claude, I used to build very detailed product specs documents (following Harper’s LLM codegen hero’s journey guide, with Codex now, it’s changed. Instead I just write a “product vision” document. This helped set expectations on the vision I want to build the product towards. This was also 100% written by me without any AI agents help, as this was something I could uniquely contribute. Plan mode was just plain boring, as I was not so excited to create a 50-point to-do lists to build MVPs. I started feeling almost like a mechanical turk blindly pressing “continue continue continue..” ad infinitum without sharp thinking. This process of taking the complete idea as input and then delivering an output was stripping me of my creative process and wasn’t really working well for me. Now, I just start with the boilerplate starter kit and ask questions based on various user stories.. I would say something like “I want users to sign in with Google” and it builds it. then I’m like “I want users to be onboarded on how to use this service” and it builds an onboarding page. one by one, one user story at a time until I build an MVP.

- break your app down into what users actually do. “a user can sign up with email and password.” “a user can create a new post.” “a user can see a feed of all posts.” this is the language the ai understands. this is how you communicate clearly.

For product vision drafting:

Ask me one question at a time so we can develop a thorough product vision for this idea. Each question should build on my previous answers, and our end goal is to have a detailed product vision, I can hand off to all of you (agents) to provide a direction of the north star. Let’s do this iteratively and dig into every relevant detail. Remember, only one question at a time.

Here’s the idea: [insert idea here]- No matter whatever code is written, TDD is still a must. LLMs can still make errors. I instruct them to write tests, and I read through the test scenarios to cross check if the user journey logic is intact.

- As I’ve now started to build more projects, I have them all neatly organised within a /Projects folder with various projects under them. /Project 1, /Project 2 etc.. If I run into an error which I’ve encountered in a different project that I’ve solved, I reference feature X and it’s implentation from Project 1 into Project 2 and it does it neatly. Over time, as we accumulate exposure to more problems solved by means of LLMs, it almost becomes an art of “compound engineering”, where previous solutions, solve current problems

- For more “harder” problems to implement, or for new feature implementations, I break the prompts into three parts. Act one would be to research potential ways to integrate the feature where I ask codex to come up with three directions, from which I pick one. Act two, involves asking Codex how it aims to build it, and the series of steps it would entail. Knowing this helps me steer Codex better. Act three involves executing it’s plan. While Act three is ongoing, I do keep an eye on what it’s doing. If something seems fishy, I either abort the operation, or ask followup questions for it to look closely. This was popularised by Dexter Horthy from Human Layer, and is a nice way to separate (research) (plan) and (execute) into different operations for clarity.

- For vibe coding on mobile, I initially attempted to run a Tailscale server, where I install a headless Claude Code CLI on a VPS server with which I can text over phone via SSH.. however this was quitew slow, and I didn’t enjoy the experience as much. For now, I just use Codex web to chat and create PRs.. once I’m back at my desktop, I just code review the PRs and merge them with the codebase…

- I’ve also been exploring skills. I recently built a “Wes Kao writing” skill to improve my executive communications at my day job. This was a custom skill fed on all the blog posts written by Wes Kao, and gives much more refined feedback on how I could improve my first drafts in business comms.. I’ve also been using Claude’s frontend-skill for instructing agents with building UI better.. I’ve seen tons of resources (such as this one, but haven’t caught up yet)

Most of these ideas I’ve learnt from Peter Steinberger, Ian Nuttall as well as Tal Raviv / Teresa Torres on Linkedin have also been inspirational to understand how to approach building with AI agents from a product lens. (I recently found Teresa’s “build in public” updates on her recent AI interviewing tool to be quite motivating)

What I haven’t explored yet (but would try soon)

- To run pre-commit hooks. The robots are very eager with making elaborate number of changes, and pushing commits. And this behavior does pollute the Github actions with various linting, formatting, and type checking errors. One way to solve this is by means of a pre-commit hook. This can be easily installed via uv tools install pre-commit command and then just build out a nice .pre-commit-config.yaml file..

- For instructing Codex on UI improvements such as “add padding”, “fix borders”, “change font” etc.. along with screenshots on where the change needs to happen. I’m planning to try the docs:list script to make these easier. It forces the model to read docs, and also stay up-to-date.

- I’m also yet to try agentic coding on mobile. Top on the list is Happy Engineering which has a great UI..

- Not really tried any form of MCPs yet, but wanting to try either the Playwright MCP, or Chrome Devtools MCP for browser automations. Screenshotting images of the UI for various tasks seem quite painful at the moment. Not sure if it should be an MCP, or a Skill that should be tasked to do this.

- 99% of the code in the codebase is written by the agents, but for the remaining 1% I would still need to manually edit the files using an IDE. For this 1%, switching windows across to Cursor IDE seems to be a lot of context switching which I hate. Wanting to try a native terminal editor that’s not having a steep learning curve. Tried neovim but was struggling to learn it well. Planning to try Fresh, which, as it’s name suggests, seems to be quite a fresh take on a terminal editor.

- So far, I’ve been purely building apps with Codex CLI, and I suspect this might also evolve or change over time. I’ve been seeing folks doing various experiments with an abstraction layer on top of such Headless CLIs.. Steve Yegge in his recent essay, describes these increasing abstraction levels as a spectrum, and as follows:

Stage 1: Zero or Near-Zero AI: maybe code completions, sometimes ask Chat questions. Stage 2: Coding agent in IDE, permissions turned on. A narrow coding agent in a sidebar asks your permission to run tools. Stage 3: Agent in IDE, YOLO mode: Trust goes up. You turn off permissions, agent gets wider. Stage 4: In IDE, wide agent: Your agent gradually grows to fill the screen. Code is just for diffs. Stage 5: CLI, single agent. YOLO. Diffs scroll by. You may or may not look at them. Stage 6: CLI, multi-agent, YOLO. You regularly use 3 to 5 parallel instances. You are very fast. Stage 7: 10+ agents, hand-managed. You are starting to push the limits of hand-management. Stage 8: Building your own orchestrator. You are on the frontier, automating your workflow.

I haven’t ventured into these stages personally in 2025, and I’m also not sure if things would change in 2026. Stages 7 and 8 are still very controversial, and debate-able right now, and is still not ripe enough for even the early-adopter’s “adoption”. Agent orchestration seems be the hottest word right now in such AI-pilled dev circles and I’m curious how this would unfold..

Wrapping up 2025..

As 2025 ends, and a new year begins, it feels that everything is possible. It’s the “age of the builder” and understanding “how to write code syntax” is no longer the bottleneck. This is also likely going to be one of the most important decades in human history, and even ordinary actions like “putting an essay on the internet” can be extremely high leverage.

Aiming to think hard about what we’re doing, and post more, write more, participate more in 2026!